Overview

When studying topics involving intrigue, secrets or subterfuge, present students with the essence of the story in the form of a coded message familiar at the time. Challenge them to decode the message to engage them effectively from the outset.

Case Studies

Lady Jane Grey (Caesar Cipher)

The famous “nine days’ queen” is Lady Jane Grey who briefly thwarted Mary Tudor from claiming her rightful inheritance following the death of her brother, Edward VI. When studying this curious chapter in British history, I provide students with an encoded (fictional) communication from the lead conspirator, the Duke of Northumberland (Jane’s uncle) outlining that Edward has died, explaining why it’s necessary to ensure the Protestant succession against the Catholic Mary given recent events, and asking for support. You can quickly encode such messages using the free online tool I have written especially for this purpose (www.activehistory.co.uk/codebreaker). I then explain to them the principle of the “Caesar Shift Cipher”, which involves encoding each letter by shifting a set number of places along by a certain number of letters, looping back to the start of the alphabet if necessary (e.g. “+3” would mean A became D, Z became C and so on). The method is named after Julius Caesar, who apparently used it to communicate with his generals.

Babington Conspiracy (frequency analysis)

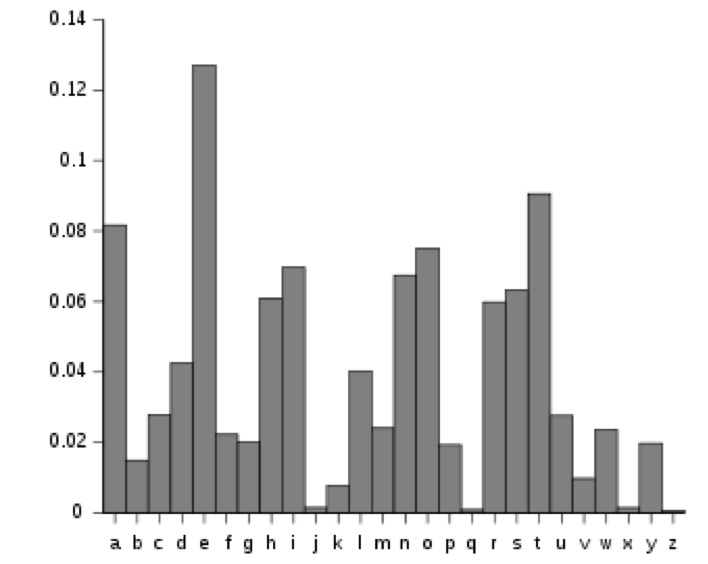

Later on, when students are studying the Elizabethan period, I enjoy teaching them about the Babington Conspiracy, an attempt this time to replace the rightful Queen of England with the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots. The difference here is that the code used wasn’t a simple Caesar Shift (which only has 25 possible permutations and so is relatively easy to ‘crack’) but involved substituting each and every letter of the alphabet with a unique symbol. The possible amount of permutations is therefore: 25 X 24 X 23 X22…all the way to X1. It’s good fun getting students to guess how large this number will be! To crack the code this time, students can be introduced to the concept of frequency analysis, pioneered by the Arab polymath Al-Qindi of Baghdad (800-873AD). He realised that certain letters occurred more frequently within language than others. In English, for example, “E” is the most common, followed by “T”.

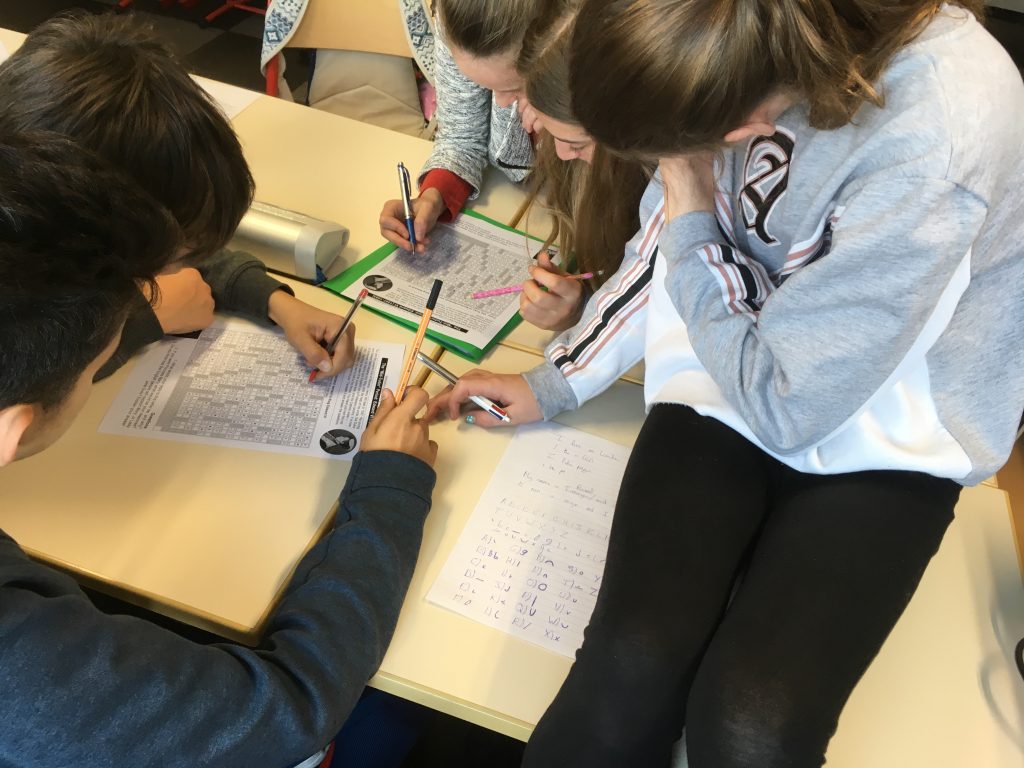

Therefore, the symbols in the encoded message will appear in the same proportions, and in this way the code can be cracked (a simple way to demonstrate the principle of frequency analysis is to ask everyone in the class to raise their hand if they have the letter ‘E’ in their name. Then get all those with a ‘Z’ to raise their hand).

I then proceed to give students an encoded version of the essence of Babington’s murderous proposal to Mary Queen of Scots (in reality several letters were sent between them whilst she was under house arrest, which were all intercepted by Elizabeth’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham). The simplest way to do this is to type your message into a word processor and then choose a gobledegook font such as ‘Wingdings’ which will instantly create your own coded message. Give students a little while to identify the most common symbols and start to decode it. When the momentum starts to run out, give them a little hint: for example, there are only two one-letter words in English – ‘A’ and ‘I’ – so a lone symbol between two spaces must be one of those two things. Similarly, the most common words of three letters in English are ‘the’ and ‘and’.

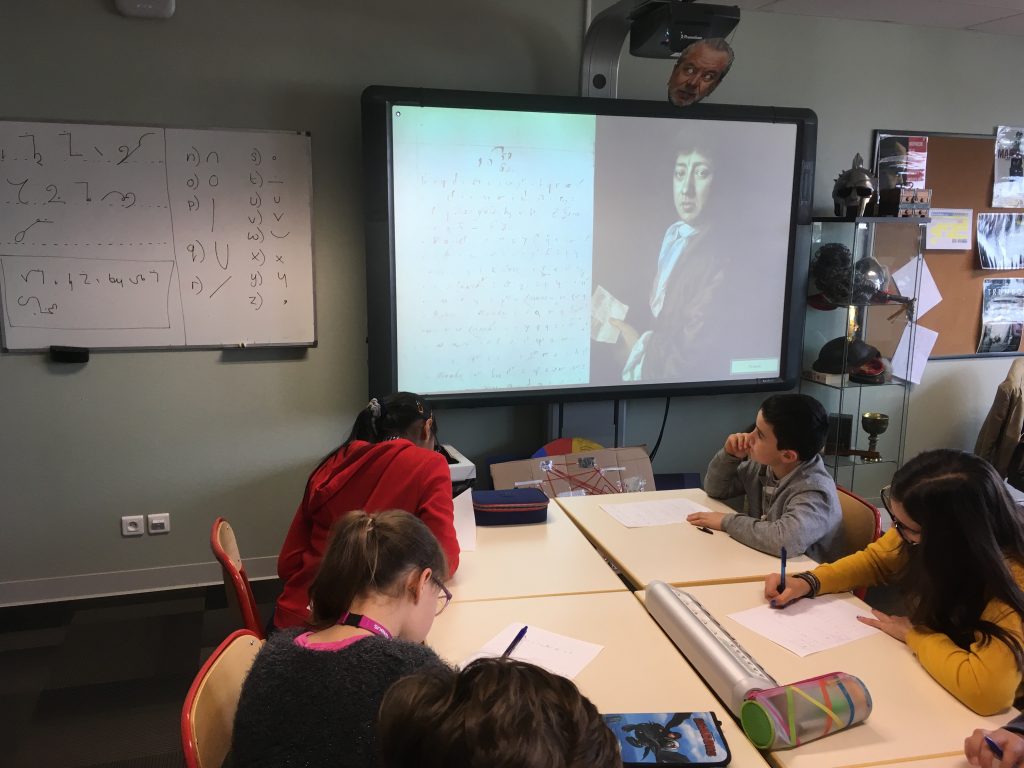

Samuel Pepys (shorthand)

Moving forward a little more in time once again, I love introducing students to Samuel Pepys, the great chronicler of the Great Plague and the Fire of London. The secret code he used for his wonderfully evocative diary was simply a form of shorthand, which is a brilliant skill to share with students to help them with their note-taking. I show the students first of all an image of one of the pages of his diary so they have an idea of how he wrote. I then explain how the basic principles of shorthand operate. First of all, remove all vowels from the words, unless the word starts with a vowel. In this way, the amount of writing has been substantially reduced at a stroke, and yet “y wll fnd tht th mssg is stll qt esy t undrstnd”. Next, each letter is converted into a simpler symbol, and the message is then written in joined writing to create a message.

At this point, I display a message on the board using the system and challenge them to decipher it; then to write their own messages using the system and swap them around to see if they can decipher those of each other. Invariably the students get thoroughly drawn into the exercise and some of them have reported to me that they proceeded to keep a secret diary for some time afterwards using the code, and still use it to take notes during lectures. History and study skills joined up perfectly!

Taking it further

I have limited the history of codes and codebreaking here to examples from the 16th and 17th centuries. Students could then be asked to find other examples from other periods: for example, older students could research Room 40, Britain’s top secret codebreaking department in the First World War, responsible for decoding the Zimmerman Telegram which helped to bring the USA into the war. Similarly, the cracking of the Enigma codes by the codebreakers at Bletchley Park is a fantastic subject of study (and allows for some LGBTQ History if then expanded into a study of the life and career of the genius Alan Turing). The Navajo code talkers are another great subject of study from World War Two.

Students could also use the study of codes in history as a way of looking at other languages and communications systems: for example Braille and Morse Codes; Mayan, Babylonian and Roman number systems; Egyptian hieroglyphs.